The last few weeks in India were tumultuous, all because of a statue, the tallest statue in the world—the Statue of Unity. The political and social circles have never seen such rife discussion, not in the least for the more pertinent issues. You would assume that in a country like India, where you can find a statue at every nook and corner, one more statue would be close to a non-existent issue. But this particular statue has been the discussion point on every news and media channel for the past few weeks. The liberal left and most opposition parties see this statue, which cost around 3000 crores (30 billion rupees) as an exercise in extravaganza, in a country where around 30 percent of the population live below the poverty line, whereas the ruling right says that this is an affirmation of the nationalistic identity and aspirations of the people, and an opportunity to generate revenue through tourism. But let’s face the facts—the real reason for opposing or supporting the statue has nothing to do with the common man. It has more to do with what it symbolizes. That is evident from the fact that even those who opposed this statue are now planning to commission even taller statues in the states ruled by them. The ruling party has presented this statue of a person, whose stature is no less than that of the first Prime Minister of India, as a symbol of non-dynastic politics and true nationalism and thus to further symbolize the possibility of a glorious India without the disruptive influence of a family that has ruled India for the last 70 years, as they say. The chief opposition party sees this as a symbol of manipulation by the ruling party for their selfish gains—an attempt to appropriate a person (and what he symbolizes) once associated with them. Never before has symbols such as statues become so important in India.

But if we look around, we are surrounded by such symbols. As I often tell in my class: a policeman or a policewoman in plain clothes does not terrify us (if we are breaking any law) as much as the same person in uniform does. It’s the power and the authority symbolized by the uniform that changes our outlook towards that person. Symbols have significance—and power. The idea of a Statue of Unity to invoke and symbolize nationalistic pride in the hearts of a billion Indians is not a new idea—it is borrowed fairly and squarely from the Statue of Liberty in New York, US. The Statue of Liberty, gifted to the United States by France, serves as a symbol to remind them of their similar history of oppression, and of liberty from it, especially in the context of both countries—the American War of Independence and the French revolution, which gave the country it’s official motto- Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite.

Years prior to the age of grandiose, opulent cathedrals and monuments in Europe and other parts of the world, Christians gathered around and identified themselves with symbols of a significantly humbler nature—the fish, the cross, the bread and the wine—to name a few.

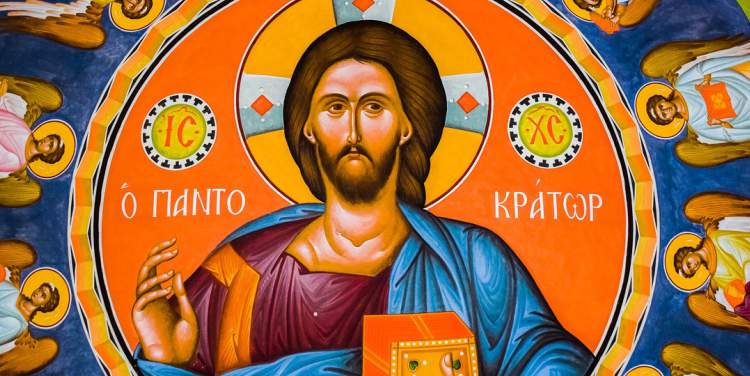

But where do we, as Christians, stand in this discussion? What do these symbols mean for us and more important—what are our symbols? Years prior to the age of grandiose, opulent cathedrals and monuments in Europe and other parts of the world, Christians gathered around and identified themselves with symbols of a significantly humbler nature—the fish, the cross, the bread and the wine—to name a few. One of the most common symbols in the early church, of which the significance is known to few today, was two arcs intersecting to form the profile of a fish. The symbol of the fish was widely used across the church, to the point that it was used by Christians to identify fellow Christians, and to mark secret meetings places and catacombs, during persecution by the Roman Empire. The symbol of the fish was very significant for the early church as it was connected to Jesus in various ways and so it reminded them of their history and the life and ministry of Jesus. Some of the early disciples of Jesus were fishermen. Jesus called his disciples to be the fishers of men. One of the earliest miracles of Jesus was the huge catch of fish. Jesus multiplied five loaves and two fishes to feed the five thousand. The Greek word for fish (ichthys) also served as an acronym for Iēsous Christos, Theou Yios, Sōtēr (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour) thereby declaring the beliefs of the early Christians about the twofold nature of Jesus Christ.

But symbol of the fish was not all that they had. The cross also became a symbol for the early church, to the point that Romans accused Christians to be adorers of the cross, an accusation countered by Tertullian as he pointed out that it was not the cross, but the saviour on the cross who was adored by the church. It is significant that a Roman instrument of humiliation and brutality, something that was reserved only for the worst criminals, slaves and enemies of the state, and a Jewish symbol of curse, became a symbol of hope and salvation for the early church. One of the most important symbols of the church was given by Lord Jesus Christ himself—the bread and the wine, signifying the sacrificial ministry of Jesus Christ. Apart from these, the teachings of Jesus used symbols from the everyday life—the sheep and the shepherd, the vine and the branches, the bread, the stone, the seed and so on. These symbols served as important reminders to the nature of the ministry of Jesus, and the nature of the church, and they serve the same today.

In a stark contrast to today’s world where even Christians, let alone the world, are attracted to display of power, glamour and opulence, the common, humble symbols of the early church pointed to their saviour, the saviour who left every privilege and position, and came down in humility to this world. It reminded them of the Son of God, the Second Person of the Trinity, who descended to the lowliest of places so that humanity can ascend with him to the highest of places. Let this Christmas be a reminder to us of the same.