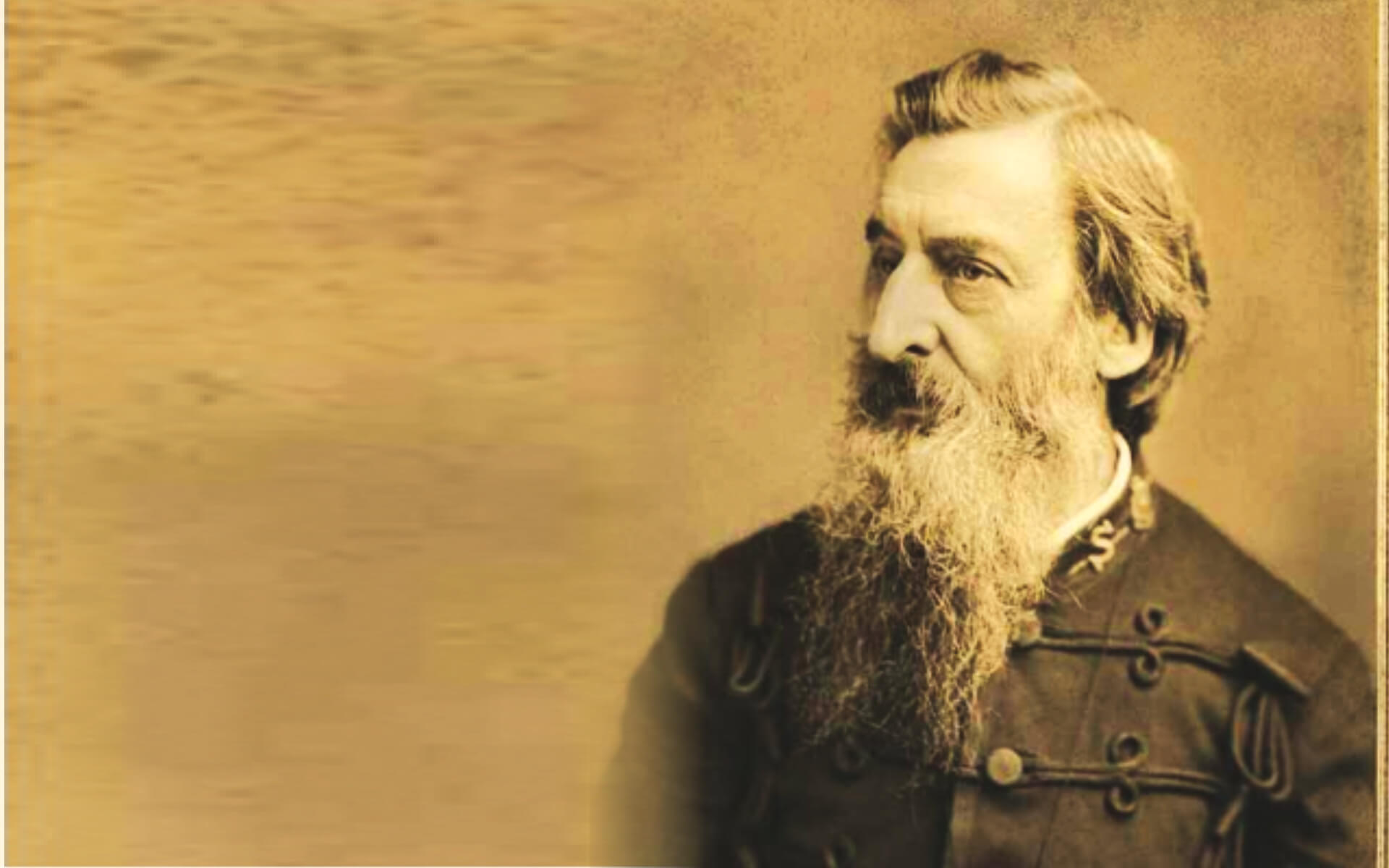

The Salvation Army completed 138 years of its arrival in India on 19th September. Major Frederick Booth-Tucker landed in Bombay along with three other ‘comrades’ on the same day in 1882. Though their arrival was comparatively late in the Protestant Mission enterprise to India, it was significant, as the test of time would prove later.

The arrival of a different ‘Army’ raised suspicion and commotion. The newspapers reported their every move in great detail. Colonial authorities, who knew about their work in their own country, were both ashamed of the “gimmicks” of the Army, which included an army-style band, a peculiar uniform and a flag, and alarmed at what these could mean for India. The four comrades were immediately arrested and prohibited from carrying out their activities. During their trial, help came from unexpected quarters. Keshub Chandra Sen, leader of the Brahmo Samaj then and a skilled orator, for instance, sent his “fraternal love and cordial good wishes” and stood ready to “protest against the cruel and unjust treatment” they were facing. Tucker and his friends were soon released.

Colonial authorities, who knew about their work in their own country, were both ashamed of the “gimmicks” of the Salvation Army—which included an army-style band, a peculiar uniform and a flag—and alarmed at what these could mean for India.

Tucker’s perceptive eye immediately made him notice the gulf between the cities and villages of India. He realised that 90 per cent of Indian population lived in villages, and if India was to be reached, it would be through its villages. He also felt that the missionary efforts to reach India’s villages were superficial. The European missionaries, including those of Salvation Army, he said, either preferred to settle in the cities, or when required to visit villages, carried the comforts of the city to villages. This was far from the call of General William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, who wanted his missionaries to “get into the skins” of their audience. What followed was drastic changes to lifestyle, beginning with a change in name. Now known as Fakir Singh, Tucker hanged his English boots to first walk barefoot and then use Indian sandals, wore a shoulder-cloth and dhoti, travelled by third-class instead of those coaches assigned for European travellers, bathed at village wells, ate with hands, cleaned teeth with sticks of a tree, begged for food, slept on the floor and later, to make travelling lighter, renounced blankets for sacks. For Tucker, this “fakirism” was not about external change, it was rather about renouncing one’s prejudices and “boldly crossing to the other side and finding out by actual experience” what is expedient for the missionaries and what is not.

Tucker and his followers made remarkable progress in the years to come, especially in Gujarat, where they began their educational system, with boarding homes, industrial schools or vocational training centres for both boys and girls, with special emphasis on teaching handicraft. They also then founded medical centres, hostels for the blind, food relief for the famine victims, sinking of wells and establishing ‘land colonies’ to settle the poor. Like Booth, Tucker saw social uplift as a crucial aspect of salvation. He genuinely appreciated the handicraft of poor Indians, and was interested in honing their skills. His efforts to promote silk production and weaving in India helped the poor find employment. He pioneered in starting as many as 22 village banks that lent money at low interest to the poor so that they could buy land.

Tucker’s perceptive eye immediately made him notice the gulf between the cities and villages of India. He realised that 90 per cent of Indian population lived in villages, and if India was to be reached, it would be through its villages.

All these came at a personal cost. In 1887, he lost his first wife, Louisa, during a cholera epidemic in India. In 1888, he married Emma, daughter of William and Catherine Booth. With Emma, he had nine children, but three of them died while still infants. He then lost his second wife in a train accident in 1903. He was married for a third time to Minnie Reid. After that he was actively involved in one of the most assiduous tasks undertaken—that of reforming the so-called “criminal tribes”. His efforts in this direction impressed and inspired many, including Arya Samaj, to take up similar endeavours.

Tucker was awarded Kaiser-e-Hind in 1913 for his service among the poor. Owing to his poor health, he moved to England in 1919 and breathed his last in 1929.

The name of Frederick Booth-Tucker has not yet made it to the case studies of contextual theology in seminaries or elsewhere. Systematic study of Salvation Army itself, with its development as an offshoot of holiness movement and its doctrines still remain little explored and often misunderstood, if not ignored altogether. An overview of Tucker’s efforts shed some light on its significance, and calls us not to discard it as one of the movements “on the fringes” that does not deserve any reflection or engagement.