A lot can be guessed about a culture by the quality of its literature.

A lot can be guessed about a culture by the quality of its literature.

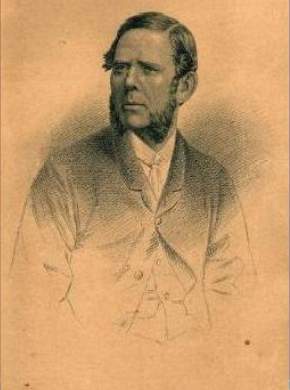

Modern Gujarati literature (1850 till today) owes much of its origin and growth to the pioneering work of Alexander Kinloch Forbes (1821–1865). A Scottish officer working with British East India Company, Forbes arrived in Bombay in 1843 and was later appointed as Assistant Judge in Ahmedabad. As a Christian, he was convinced that his arrival in India was providential.

In 1848, almost two decades before Karan Ghelo, the first Gujarati novel, was published, Forbes along with a few friends, founded Gujarat Vernacular Society (GVS). The aim was “promotion of Gujarati language and literature, diffusion of useful knowledge and growth of general education.” The contribution of GVS was monumental in two ways: encouraging literature in local language, and promoting literature as a means for social reform.

GVS became a catalyst in heralding a new age in Gujarati literature and, consequently, speeding up social reform throughout the region. Forbes’ initiatives through GVS introduced forms like essays, memoirs, sonnets and novels in literature. It started Ahmedabad’s first Gujarati newspaper, Vartmaan, famously known as Budhvaariyu because it was published every Wednesday (Wednesday being Budhvaar in Gujarati). In regard with social reform, GVS started Gujarat’s first school for girls, a public library (only second in the state, the first was in Surat), first literary magazine known as Buddhiprakash, and first literary society called Vidhyabhyasak Mandal.

One of the foremost Gujarati poets who heralded modern age in Gujarati literature was Kavi Dalpatram. Forbes was a very close friend of Dalpatram, and the latter’s rise in Gujarati literature owes much to Forbes. Interestingly, Dalpatram was naturally inclined to compose in Brajbhasha, since Gujarati was often considered a bazaar language used by Baniyas and not worthy to be used for serious writing. Forbes, however, was convinced that writing in local language was crucial, as that would provide larger platform for the dissemination of ideas. He wanted to learn Gujarati himself and also encouraged Dalpatram to write in Gujarati. For Forbes, however, literature in vernacular language was not merely an aesthetic gratification; it was rather a “religious obligation.” Achyut Yagnik, a Gujarati sociologist, in his book The Shaping of Modern Gujarat, quotes this conviction in Forbes’ words,

“When we contribute to a Christian Mission we acknowledge the call. When we try to lift up the language of the province from its present ignoble condition and encourage the more gifted fancies among those to whom it is vernacular, to enlarge, refine and regulate it by manifold application, that it may become fitter to convey from mind to mind and from generation to generation both the beautiful and the true, then too we acknowledge the same call to benefit those among whom for the present we are sojourners.”

Far from being a colonial agenda to suppress the language of the colonized, encouraging vernacular literature, for Forbes, was a theological conviction. ‘The beautiful and the true’ needed to be conveyed, and it was to be conveyed in the language of the masses.

Far from being a colonial agenda to suppress the language of the colonized, encouraging vernacular literature, for Forbes, was a theological conviction

In 1858, Forbes compiled his Rasmala, a two-volume compilation of the history of Gujarat, a collection of texts and tales from bardic, Jain, Persian sources and from the folklores of Gujarat. In addition, GVS organised writing competitions and gave cash prizes to those writing historical essays. This provided impetus to the writing of local histories; in fact, the first systematic history of Ahmedabad was written as a part of this exercise. This was to become a force in persuading people to think about their own history, which in turn would sow the seeds of nationalism and regionalism.

It would not be an overstatement to say that the social concern in modern Gujarati literature was the direct result of Dalpatram rubbing shoulders with Forbes. Dalpatram travelled across length and breadth of Gujarat to assist Forbes in writing Rasmala, witnessing the realities of Gujarati society, which then became crucial to his poetry. Realism took over the literature by storm; widows, women and children became heroes of novels.

The life and contribution of Alexander Forbes is significant for us in two ways. Firstly, it is a timely reminder to our generation that Christian convictions have played important role in the transformation of our nation; lest the many voices crying out against it today not convince you otherwise. Secondly, the same convictions as that of Forbes can bless our nation today, if we realise that all our efforts, all our careers, all our services, regardless of the field we are involved in, are regulated by and directed to the single aim—that of serving our Master and, in Forbes’ words, “to benefit those among whom for the present we are sojourners.”