The month of March 2020 was a shocker in the Indian political circles. It was one of those events that everyone saw coming, but nobody thought would actually happen. Jyotiraditya Scindia, the scion of the erstwhile royal family of Gwalior and the son of Madhavrao Scindia, left the political party he was raised in—for all intents and purposes. His father was a stalwart of the Congress party and he himself was a close confidante of Rahul Gandhi, the former (at the time of writing this article) president of the Congress Party. When the dust around the political storm settled, one question lingered in everybody’s mind—was it that easy for him to leave an ideology that he was raised up with, something that he championed as recently as the previous month? While we may not have a definitive answer to that anytime soon, a similar question must pervade the mind of every thinking Christian, when they look at the sheer number of Christian denominations out there—is it that easy for people to leave a church/denomination to join or start another?

According to the World Christian Encyclopedia (WCE), first published in 1984, “World Christianity consists of six major ecclesiastico-cultural blocs, divided into 300 major ecclesiastical traditions, composed of over 33,000 distinct denominations in 238 countries.” Now, the definition of a denomination and the list given by WCE has been called into question many times, the reason for which is evident when one goes through the list of denominations given there. But even if we take out all those denominations that wouldn’t be traditionally considered as orthodox from this list and conflate those that should belong together as one, there are still a sizeable number of denominations left. So, the question is—how did we get here, from a tight-knit group of followers that we see as the First-Century Church in the book of Acts? After all, don’t we all believe the same thing—that “… “Jesus is Lord,” and believe in (y)our heart that God raised him from the dead…” (Romans 10:9)? Is it that easy to break away from a denomination and start one’s own? The answer is not as straightforward as one might think. Luther, who’s often pictured as an impatient man waiting for a straw to break away from the Catholic church, certainly didn’t think so. In fact, theses’ 48–52 of Luther’s 95 theses clearly show that he was hoping for a renewal, rather than a split, within the Church.

When Martin Luther questioned the limits of papal authority and the clergy in 1517… he wasn’t disputing the leadership structure of the Roman Catholic Church. The questions that he raised… were primarily theological in nature connecting the doctrines of Salvation, Scripture and the Church, to name a few.

If we go back in ecclesial history and look at the major divisions that happened in the Church, the questions at the heart of each dispute have been theological in nature. Even issues that seem practical in nature have a theological fundamental. For example, when Martin Luther questioned the limits of papal authority and the clergy in 1517 and subsequently split from the Roman Catholic Church, he wasn’t disputing the leadership structure of the Roman Catholic Church. The questions that Martin Luther raised in the now famous 95 Theses were primarily theological in nature connecting the doctrines of Salvation, Scripture and the Church, to name a few. Prior to the Reformation, we had the Great Schism in 1054 (also known as the East–West Schism), which was a major split in the Church dividing the Church into two—the Western Church (which later came to be primarily identified as the Roman Catholic Church) and the Eastern Orthodox Churches—due to both theological and political issues.

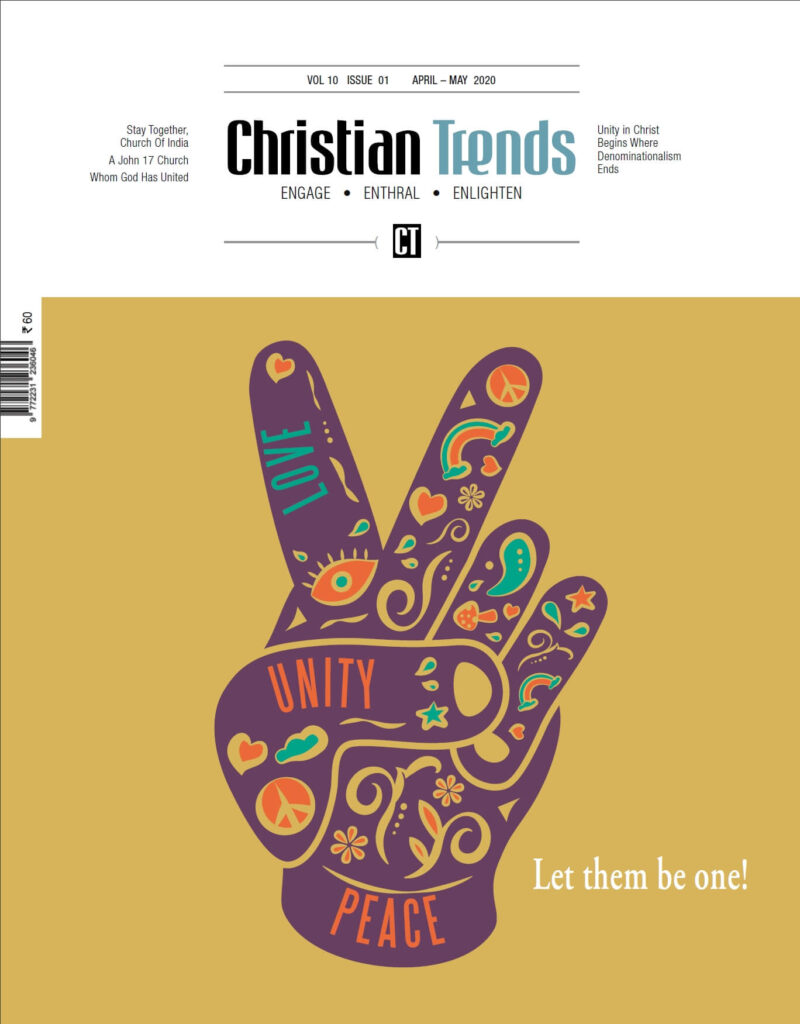

In such a context, it may seem that we are at a point of no return, where it’s just impossible to bring everyone together and the idea of a “one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church” as expressed in the Niceno-Constantipolitan creed seems like a distant dream (please note that catholic here doesn’t refer to the Roman Catholic Church). However, in this fast-paced world with its plethora of idea and ideologies, where churches and denominations are split at the whims and fancies of individuals and sheep-stealing is the norm of the day, the need of the hour—more than ever before—is for the churches around the world to find a way to come together, despite their differences. Two helpful paradigms can help us navigate the rocky waters of the modern-day intellectual environment—koinonia and oikoumene.

Paul spells out the fundamentals of the household of God—One Body, One Spirit, One Hope, One Lord, One Faith, One Baptism and One God and Father of all—which should clarify certain theological points when it comes to interdenominational disputes.

Koinonia, a Greek word that is often seen in the New Testament,refers to communion or fellowship and it is used in many different contexts, perhaps the most significant of which we see in 1 Corinthians 10:16–17, where Paul uses it to signify our communion with Jesus Christ and with fellow believers. Paul uses the term koinonia here to point out that when we partake in the Lord’s Table, we have communion and fellowship with believers from all over and not just with ones who are immediately present before us. In fact, the whole of 1st Corinthians is an excellent example of how the believers can come together in communion despite their differences. The Early Church depicted this attitude in Acts 15 when they came together to find a resolution for a theological dispute that arose regarding the faith of the gentile believers. The Lord’s Table (or the Eucharist) signifies and must serve as a constant reminder to us that we are all parts of the same body in communion under the common headship of Lord Jesus Christ.

The second important paradigm which can help the Church to come together is from another Greek word that we don’t encounter as often in the New Testament—oikoumene. While the word itself means “the whole inhabited world”, theologically it has come to refer (along with oikos) to the household of God with a global emphasis, as we see in Ephesians 2:19. Paul, in his letter to the churches in the region of Ephesus, affirms that they “are no longer foreigners and strangers, but fellow citizens with God’s people and also members of his household.” Paul drives his point home about the oneness of the Church as a family under the authority of God the Father in Ephesians 4:3–6. He says,

Make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace. There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to one hope when you were called; one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.

In verses 4–6, Paul spells out the fundamentals of the household of God—One Body, One Spirit, One Hope, One Lord, One Faith, One Baptism and One God and Father of all—which should clarify certain theological points when it comes to interdenominational disputes. The idea of oikoumene reminds us that we are part of God’s global family irrespective of where we are, thereby placing the onus all the more on us to find ways to come together as a family.

So, to come back to the initial question—is it that easy? It should be as easy as tearing a body apart—which is—it shouldn’t be! If we find nothing wrong with such a phenomenon, then there’s something fundamentally wrong with our theological outlook. I am well aware that none of the paradigms suggested here resolve any of the theological and practical differences that exist between different denominations (to find help in that area, read the excellent article by my colleague, Stephen Paul, in this issue). I’m hoping that it provides us with the spectacles of love to view others favourably, thus helping us to come together as the body of Christ and the family of God.