“Was Michael Jackson a paedophile?” has been a much-debated topic. Leaving Neverland, the highly controversial documentary surrounding child molestation claims against Michael Jackson, has rekindled that conversation. The issue has also raised questions like ‘Should his music be banned? Should we stop talking about it? Should artwork be banned with the artist?’ MJ’s music is legendary and to quote Alexis Petridis (Critic, The Guardian), “Too many people have too much of their lives bound up with his music.” How does one then separate the artist from his art? The way people seem to have done it is by compartmentalizing these two aspects. I suppose, as a fan, it is traumatizing to acknowledge that someone you idolize could be capable of evil.

Paedophilia seems to be an open-and-shut case as far as judgment over its “wrongness-quotient” goes, whether in the Christian world or outside. Consider now extra-marital relationships. The responses to it may be mixed but within Christian circles, it’s a clear sin. Keeping this in mind, consider Karl Barth and his relationship with his secretary and his alleged mistress Charlotte von Kirschbaum.

Have we stopped using Barth’s books? Has he been struck off the annals of Christian theology? I doubt it and that is not even the question? What we see is the same intriguing pattern as observed with MJ fans. Karl Barth and his writings are compartmentalized, the writer is separated from his writings—judgement swirls him, the usage of his writings is debated upon.

This isn’t about MJ or Barth. It isn’t about paedophilia or illegitimate relationships. It isn’t about music or theology. It isn’t about Christian or secular. It’s about what we as humans seem to do when certain subjective experiences become too hard to bear and how we reconcile ourselves with them in order to still be able to engage with them.

We tend to silence the uncomfortable narrative in favour of the one that can be universally enjoyed and celebrated and that our conscience can comfortably sit with.

Dissociation, a psychological term, is a defence mechanism unconsciously resorted to, often in traumatic experiences, to split off from reality when it gets too hard to bear. In the case of MJ or KB, or any such person you may choose to think of, while what occurs is not dissociation, there is a detachment from difficult reality, a separation of the two conflicting realities about the person—for instance, if the person is my abuser, then separate that he is my loving, kind, generous uncle, and at the same time rapes me at night. Likewise, if a writer or artist, then separate this man of mighty intellect and gifting from his way of life that seems to violate the faith he subscribes to. It seems to be the way we resolve our own internal conflicts about such matters.

Understandably, we need to cope. However, the danger in compartmentalizing truth is losing touch with it. It leads to building of alternative narratives that over time replace truth and increases doubt. Paradoxically, while compartmentalization seems to increase clarity, what it does is increase room for doubts to settle in over time. After all, isn’t that how narratives in history have been remembered? Separate the personal life of the historical figure from their work and achievements for that is the only way we would still be able to remember and celebrate their greatness? To the extent that when dissonant truths about that person emerge, we try and ignore those uncomfortable truths in favour of acknowledging their positive impact on history? In other words, when there are two dichotomous conflicting narratives about a person, we tend to silence the uncomfortable narrative in favour of the one that can be universally enjoyed and celebrated and that our conscience can comfortably sit with.

Humans are flawed. Some flaws—we can overlook. Those we can’t, what do we do with them? Which flaws can be overlooked, and which cannot? Generally, a person caught lying will be better tolerated than a person committing adultery. But I am not aware of any hierarchy of “sin” that God dictates. We are willing to gloss over a lie but will swear to bring down the adulterous. God, however, seems to treat both sins with equity.

Dissociation, a psychological term, is a defence mechanism unconsciously resorted to, often in traumatic experiences, to split off from reality when it gets too hard to bear.

That’s why I like the way God has allowed human history to be recorded in the Bible. We have great heroes in there, Abraham, Moses, David, Gideon, to name a few. Their acts are great, their impact seen across generations. Their sins or weakness were equally noteworthy—adultery, murder, doubt, to name the biggies, and the lies, silence that in my opinion are equally damaging. But biblical history hasn’t recorded a singular lopsided narrative about these people, dwelling only upon their great acts. Rather, an integrated narrative is presented, that holds and contains the confrontation and tension between conflicting realties about a same person and his life, thereby hopefully rendering a full and truthful account. As pastors, caregivers, counsellors, we would serve our people well if we learned to do the same. We come across people and their stories that are difficult to digest. It would be hard to treat them fairly and without judgement if we don’t learn to hold well the tension between the incongruence and duality of their narratives.

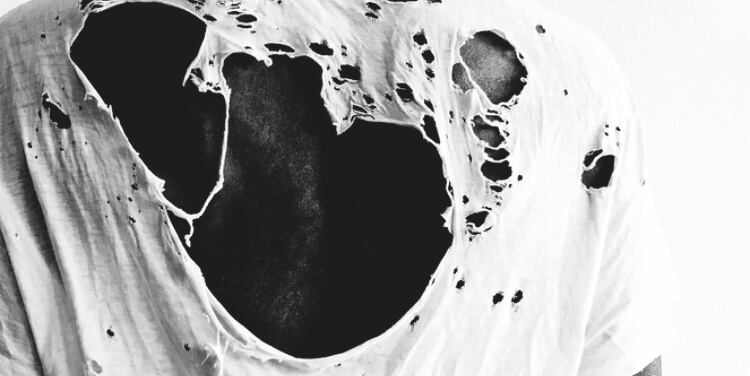

Paradigms don’t have to be two extremes—overlook or obliterate—ban the music, burn the books. There is another paradigm to consider: integrate. Rather than compartmentalize because it’s easier, let’s consider sitting with the discomfort of these coexisting realities. Let us integrate them into the narrative we are weaving for ourselves, for these individual narratives form the fabric of collective history and memory. We cannot afford to ‘dissociate’. Even in mental health practices, the goal is often time to reintegrate the narratives. One of the practices adopted to do these are exercises in being mindful and being present. That is the posture we need to adopt about events and people of our generation. Be present to what is happening. Fully. Be mindful of different realities. Attempt to weave a coherent, integrated narrative. For what we put down today as truth becomes the history of the future generations. We owe it to them to give them an undissociated, integrated account of our present times. More importantly, we owe the same to ourselves for we deserve to believe and create whole and truthful memories. And to the people in question—don’t they deserve the same?