Mental distress does not occur in a vacuum but in a socio-cultural context. The occurrence of mental illness is closely linked to sociological phenomena like poverty, caste and class stratification, ethnic and communal affiliations, gender biases, etc.

Just communicating compassion through listening holds space for the other to begin their process of healing.

Jyothi, a househelp, complained of recurring aches and pains. She visited many doctors, but none were able to help. A couple of them suggested that the pain was psychological.

Manish was addicted to alcohol. He found himself stealing money and indulging in this habit day after day. He wished someone would help, but was too ashamed to ask.

Nagma, mother of a one-year-old, unemployed and unskilled, had been abandoned by her husband. She felt rejected, lonely and scared, and longed for someone to talk to.

Jyothi, Manish and Nagma (names changed) represent common mental health struggles a majority of people, including Christians, suffer from. The pandemic has only exacerbated the existing loneliness, anxiety and violence in many lives. Further, the migrant workers’ crisis that unfolded in the wake of pandemic-induced lockdown brought to fore the enormous mental health burden in the context of the marginalised and the underprivileged people.

One in seven Indians are said to suffer from mental disorders. Globally, India is now considered a forerunner in mental health morbidities. Yet mental health does not visibly figure in our national agenda; only 0.05% of total healthcare budget—which itself is a measly 1% of the country’s GDP—is allocated to addressing mental health. Much of this is skewed in favour of pharmacological band aids that do not address the core of the problem. There has never been a more desperate need for large-scale, wholistic therapeutic interventions to restore mental health and hope for India.

Easier said than done though. There are only about 4,000 psychiatrists, 1,000 psychologists and 3,000 social workers for a population of 1.3 billion! With such paucity of mental health professionals, and most of these services concentrated only in big cities, mental health care is inaccessible to most. Further, even in cities, quality mental health care remains unaffordable to a majority of people; the cost of just one consultation ranges between Rs 200–Rs 400, beyond the means of an average household.

So, who or what then can stand in the gap? If there are inadequate social workers, counsellors and psychiatrists, how can this crisis be faced head-on?

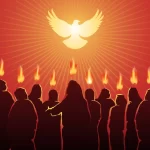

As Christians, the answer is obvious: the Church. I believe one of the key purposes of the Church is to help this world experience the wholistic healing that comes from our compassionate Creator. For at the core of our ongoing re-creation as Jesus’ resurrected body is our ministry as healers of the brokenness that is at the root of life itself. The actions of Jesus in the Gospels clearly light the way for us; the Holy Spirit embodies the counsellor and comforter today. The bedrock of love that nurtures our relationship with our triune God is the paradigm for the safe relational spaces we are to create in this ailing world.

I believe one of the key purposes of the Church is to help this world experience the wholistic healing that comes from our compassionate Creator.

What I offer below are three issues concerning mental illness that the Church should be aware of; and then, I affirm four simple ways in which the members of the Christian community, even those not professionally trained, can address the mental health issues of their neighbours.

Everyone needs help

1. We are ill ourselves: Illness is normal. Mental illness, like physical illnesses, may be temporary, or acute, or chronic and to be managed for life through strict disciplines. Like physical illness, it is a mark of our poverty and weakness, through which God’s power is made visible and God is glorified. In a world that pursues infallibility, it is a reminder that our God shines through the chinks and cracks in us.

So everyone falls ill at some point. I accessed therapy twice in my life (once as a new mother, another when I entered perimenopause). Both times, by the grace of God, I was able to access and receive exactly the help I needed. I was fortunate because I had a supportive husband, prayerful believer friends who held space for me, resources to pay for the sessions, and life circumstances that helped me process and practice what I needed to, to move on healthily.

The truth is that we are all both healer and sick, found and lost, putting off the old and putting on the new, and so, saved and being saved. This truth has to be at the centre of all our efforts to address mental illness. The Church is called to realise how flawed and imperfect, and so in need of help, each one of us ourselves is. We are called to normalise the behaviour of seeking help, by practising it ourselves. No one is invulnerable. We are called to confess our own struggles and vulnerability, first to God and then to those who can help us. The best way to become better healers is by experiencing healing ourselves. And all along, to testify to our ongoing journey to encourage our fellow travellers. We pray for sober judgement and humility to know our own vulnerabilities, and courage to seek help and to testify to our journey.

2. Stigma and culture of silence: Manish was ashamed to ask for help for a reason. Often there is a societal stigma against confessing mental distress; a culture of silence that prevents people from seeking help. People viewed as mentally ill are ridiculed; families that have a member suffering from mental distress are looked down upon. This is well ingrained in our churches too.

Jesus was up against this silence too. The gospels are replete with instances where Jesus “knew their thoughts” or “what was in her heart.” Jesus was able to see beyond the superficial to the person’s real need because he was compassion embodied. In the strength of the Holy Spirit, the Church can do this too. Since the mind-body-spirit are interlinked, the need for support is often visible in many non-verbal ways—in the eyes of the person, in their actions or inactions, in their silences, and sometimes their absences. We pray that the Holy Spirit help us to see beyond the visible and stay alert to the needs of our neighbours.

3. Socio-political causes of mental illness: Jyothi’s undiagnosable aches were not imaginings of her mind. Nor was she making up excuses for paid leave. Jyothi’s husband was a daily wage earner and unpredictable manual work meant they were invariably in deep debt. Remembering the mind-body connect, the only way this stress could manifest for Jyothi was as the aches in her body.

The poor socio-economic situation that Jyothi found herself in was not because they were not hard workers. It was the result of complex and inter-generational cultural and socio-political factors like them being born to farm labourers, who belonged to a lower caste, and had no land holdings or social standing. The recent migrant tragedies are but a glimpse of the oppression and inequalities that breed and perpetuate mental illnesses. Mental distress does not occur in a vacuum but in a socio-cultural context. The occurrence of mental illness is closely linked to sociological phenomena like poverty, caste and class stratification, ethnic and communal affiliations, gender biases, etc.

Jesus’ response in situations invariably took into account the context that the person was embedded in. We see this in his interchange with the Samaritan woman at the well, with Zachcheus and the rich young man. In fact, this is the hallmark of all of his interactions. It could be said that Jesus’ entire active ministry to lost sheep, was to those that were socio-politically contemptible. So, when we are dealing with issues of mental health, it’s not enough to view people as individuals who are suffering. We need to be aware of specific cultural issues, accommodating of realities that are very different from ours, and, casting our biases aside, be sensitive to what is of value to the person in distress. We pray that the Holy Spirit will grant us the insight to understand these broader contexts without judgement, so that our responses may be wholistic and true.

…we are all both healer and sick, found and lost, putting off the old and putting on the new, and so, saved and being saved. This truth has to be at the centre of all our efforts to address mental illness.

Everyone Can Help

1. Compassionate listening: Nagma’s trauma was deep and complex. For her to start her journey of healing, she needed somebody who would listen to her compassionately, and hold her baby for a while so she could get a break. The primary need of a human being, studies now show, is to have a sense of belonging. The deeper this rootedness, the greater our ability to heal. Today however, migration away from source communities has become a norm (rural to urban, national to international). One fallout of this is that we live in heterogenous communities; traditional rituals and practices that anchored our sense of being seem to slip away; and family and marital crises and breakdowns become more common. In our increasingly uncertain and digitised world, the sense of belonging is constantly being eroded.

Jesus promises that there will come to reside with us a comforter and guide, the seal of our salvation—the Holy Spirit. And that the Holy Spirit will ever be with us. This knowledge of the triune God never leaving nor forsaking, but always faithful, is what anchors our faith in the most trying of times. In God’s service, we are called to be present, just like the Holy Spirit, for the people around us. As a Church, we must have the ability to be freely available to walk alongside our neighbours in distress, practising active listening viz. listening in alertness and empathy. Just communicating compassion through listening holds space for the other to begin their process of healing. This space for listening can also be in the form of active prayer groups, which become safe spaces not only to listen but also to point to God’s faithfulness and comfort. We pray that we are enabled to practice compassionate listening and providing safe spaces.

2. No assistance is too small: Assisting someone in mental distress is not just about counselling. Once we are aware of the contributive factors, we can find myriad ways to help. This could be providing financial help or food or childcare. In Nagma’s case for example, just holding her baby for a while gave her a break. In Manish’s case it was involving him in works of the church. In Jyothi’s case it was holding prayer meetings in her home periodically. Helping could also be involving the person in worship singing, or decorating the church, or organising prayer sessions so there is a space to hear others who are going through similar experiences and know that one is not alone. Sometimes, these have become places where interpersonal or community disputes may be brought up and resolved. Often contextual burdens are so great, any little thing is received with much gratitude. Building relationships like this also then gives one a chance to point towards resources that could help that are beyond the Church—maybe a workshop or a counsellor or a rehabilitation centre. Even as the Spirit leads us to the Father through Jesus, we minister by pointing to where the answers are. We pray for discernment in knowing how to assist and for generosity in the things that have been given to us.

3. Upgrading our skills: In today’s world, information and training are literally at our fingertips. There are more chances today to learn how to help more effectively than ever before. So as a Church, we can work to constantly upgrade our knowledge, skills and abilities to be of better service. For example, we can together learn about “what is depression” or “how to prevent suicide” or “manage money wisely” or “stress-coping techniques” to help both ourselves and others. Throughout the lockdown there have been offerings by various resource people. Sharing these possibilities and availing of them strengthens our ability to ease mental health morbidities. We can organise and attend workshops and talks that can help us hone the gifts we have been granted. We pray that God will grant us opportunities to hone our skills so we may be empowered to serve others.

4. Humbly, glorify God: A regular at church, Vidya (name changed) struggled with anger issues: in anger she said and did things that hurt others or herself, with long-lasting consequences. We had talked about what to do on several occasions: pause, count to ten, take deep breaths, walk away… Nothing had really worked. So I prayed, asking God to give me the answer to give her. Days went by; she kept asking for an answer, and I had nothing but a listening ear. One day she came to me radiant. She said, “Didi, mera gussa abhi control mein hain.” She said that God had spoken to her and told her that every time she felt angry, to recite Psalm 23 (we had been learning that in our prayer group). She said that by the time she recited the Psalm, her anger had usually cooled down enough for her to think clearly. I was amazed and deeply humbled. I realised that the actor in all situations is God, not me. And the Holy Spirit is constantly refining me, while helping the others brought my way.

This is something the Church needs to keep at the centre. God is the actor, not us. Our God is alive, and active, right now. The Holy Spirit is the one at work. We are just conduits at best, and privileged witnesses of Jesus’ handiwork always. Our primary work as healers then is to bear testimony for God’s glory. We walk along and beside as companions with the vulnerable, following Jesus together. So we pray that God will enable us to identify and glorify divine handiwork, both in us and in our neighbours.